Queue

A special type of list is the queue data structure

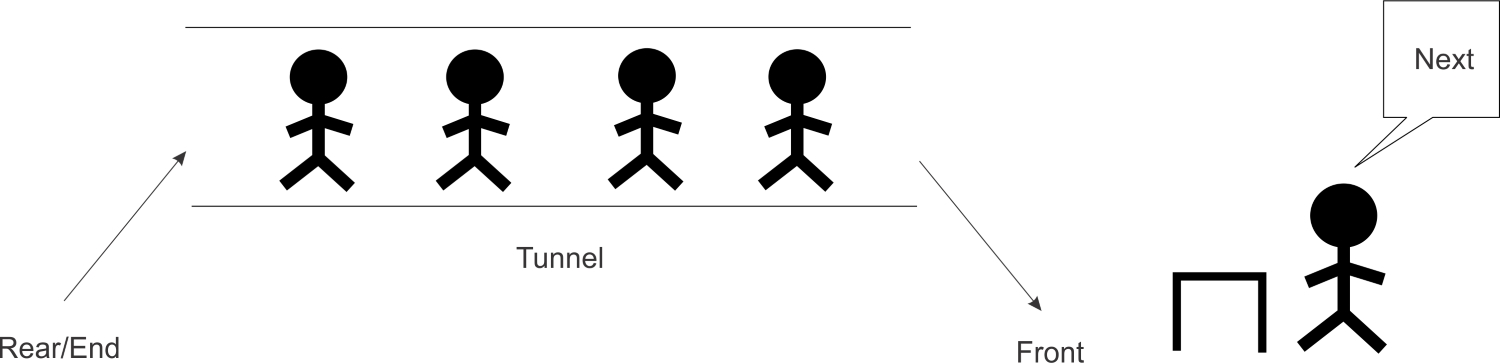

- This data structure is no different from the regular queue you are accustomed to in real life. If you have stood in line at an airport or to be served your favorite burger at your neighborhood shop, then you should know how things work in a queue.Queues are also a very fundamental and important concept to grasp since many other data structures are built on them. The way a queue works is that the first person to join the queue usually gets served first, all things being equal. The acronym FIFO best explains this. FIFO stands for first in, first out. When people are standing in a queue waiting for their turn to be served, service is only rendered at the front of the queue. The only time people exit the queue is when they have been served, which only occurs at the very front of the queue. By strict definition, it is illegal for people to join the queue at the front where people are being served:

To join the queue, participants must first move behind the last person in the queue. The length of the queue does not matter. This is the only legal or permitted way by which the queue accepts new entrants.

As human as we are, the queues that we form do not conform to strict rules. It may have people who are already in the queue deciding to fall out or even have others substituting for them. It is not our intent to model all the dynamics that happen in a real queue. Abstracting what a queue is and how it behaves enables us to solve a plethora of challenges, especially in computing.

We shall provide various implementations of a queue but all will revolve around the same idea of FIFO. We shall call the operation to add an element to the queue enqueue. To remove an element from the queue, we will create a dequeue operation. Anytime an element is enqueued, the length or size of the queue increases by one. Conversely, dequeuing items reduce the number of elements in the queue by one.

To demonstrate the two operations, the following table shows the effect of adding and removing elements from a queue:

| Queue Operation | Size | Contents | Operatn results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Queue() | 0 | [] | Queue object created |

| Enqueue "Mark" | 1 | ['mark'] | Mark added to queue |

| Enqueue "John" | 2 | ['mark','john'] | John added to queue |

| Size() | 2 | ['mark','john'] | Number of items in queue returned |

| Dequeue() | 1 | ['mark'] | John is dequeued and returned |

| Dequeue() | 0 | [] | Mark is dequeued and returned |

Visualizing a Queue is easiest if you think of waiting in line at the bank with a “head” and “tail” on the line. Usually there’s a rope maze that has an entrance at the end and an exit where the tellers are located. You enter the queue by entering the “tail” of this rope maze line, and we’ll call that shift because that’s a common programming word in the Queue data structure. Once you enter the bank line (queue), you can’t just jump the line and leave or else people will get mad. So you wait, and as each person in front of you exits the line you get closer to exiting from the “head.” Once you reach the end then you can exit, and we’ll call that unshift. A Queue is therefore similar to a DoubleLinkedList because you are working from both ends of the data structure.

Note: Many times you can find real-world examples of a data structure to help you visualize how it works. You should take the time now to draw these scenarios or actually get a stack of books and test out the operations. How many other real situations can you find that are similar to a Stack and a Queue?

Queues

If we need more control over communication between processes, we can use a Queue. Queue data structures are useful for sending messages from one process into one or more other processes. Any picklable object can be sent into a Queue, but remember that pickling can be a costly operation, so keep such objects small. To illustrate queues, let's build a little search engine for text content that stores all relevant entries in memory.

This is not the most sensible way to build a text-based search engine, but I have used this pattern to query numerical data that needed to use CPU-intensive processes to construct a chart that was then rendered to the user.

This particular search engine scans all files in the current directory in parallel. A process is constructed for each core on the CPU. Each of these is instructed to load some of the files into memory. Let's look at the function that does the loading and searching:

def search(paths, query_q, results_q):

lines = []

for path in paths:

lines.extend(1.strip() for 1 in path.open())

query = query_q.get()

while query:

results_q.put([1 for 1 in lines if query in 1])

query = query_q.get()

Remember, this function is run in a different process (in fact, it is run in cpucount() different processes) from the main thread. It passes a list of path.path objects, and two multiprocessing.Queue objects; one for incoming queries and one to send outgoing results. These queues automatically pickle the data in the queue and pass it into the subprocess over a pipe. These two queues are set up in the main process and passed through the pipes into the search function inside the child processes.

The search code is pretty dumb, both in terms of efficiency and of capabilities; it loops over every line stored in memory and puts the matching ones in a list. The list is placed in a queue and passed back to the main process.

Let's look at the main process, which sets up these queues:

if _name_ == '_main_':

from multiprocessing import Process, Queue, cpu_count

from path import path

cpus = cpu_count()

pathnames = [f for f in path('.').listdir() if f.isfile()]

paths = [pathnames[i::cpus] for i in range(cpus)]

query_queues = [Queue() for p in range(cpus)]

results_queue = Queue()

search_procs = [

Process(target=search, args=(p, q, results_queue)

for p, q in zip(paths, query_queues)

]

for proc in search_procs: proc.start()

For an easier description, let's assume cpu_count is four. Notice how the import statements are placed inside the if guard? This is a small optimization that prevents them from being imported in each subprocess (where they aren't needed) on some operating systems. We list all the paths in the current directory and then split the list into four approximately equal parts. We also construct a list of four Queue objects to send data into each subprocess. Finally, we construct a single results queue. This is passed into all four of the subprocesses. Each of them can put data into the queue and it will be aggregated in the main process.

Now let's look at the code that makes a search actually happen:

for q in query_queues:

q.put("def")

q.put(None) # Signal process termination

for i in range(cpus):

for match in results_queue.get():

print(match)

for proc in search_procs:

proc.join()

This code performs a single search for "def" (because it's a common phrase in a directory full of Python files!).

This use of queues is actually a local version of what could become a distributed system. Imagine if the searches were being sent out to multiple computers and then recombined. Now imagine you had access to the millions of computers in Google's data centers and you might understand why they can return search results so quickly!

We won't discuss it here, but the multiprocessing module includes a manager class that can take a lot of the boilerplate out of the preceding code. There is even a version of multiprocessing.Manager that can manage subprocesses on remote systems to construct a rudimentary distributed application. Check the Python multiprocessing documentation if you are interested in pursuing this further.